01 05 2023

Kyoto, Japan

Hayato & Mika Nishiyama

from Mitate

お正月飾りの中でも最も華やかな飾りのひとつに餅花がある。

飛騨高山には、つきたての餅を切り株から伸びた枝に花のように飾りつけた「はなもち」があり、長野や京都など多くの地域では、枝垂れ柳に餅をつけ、稲穂の垂れる豊作を表現した「稲の花」「粟穂稗穂(あわぼひえぼ)」がある。

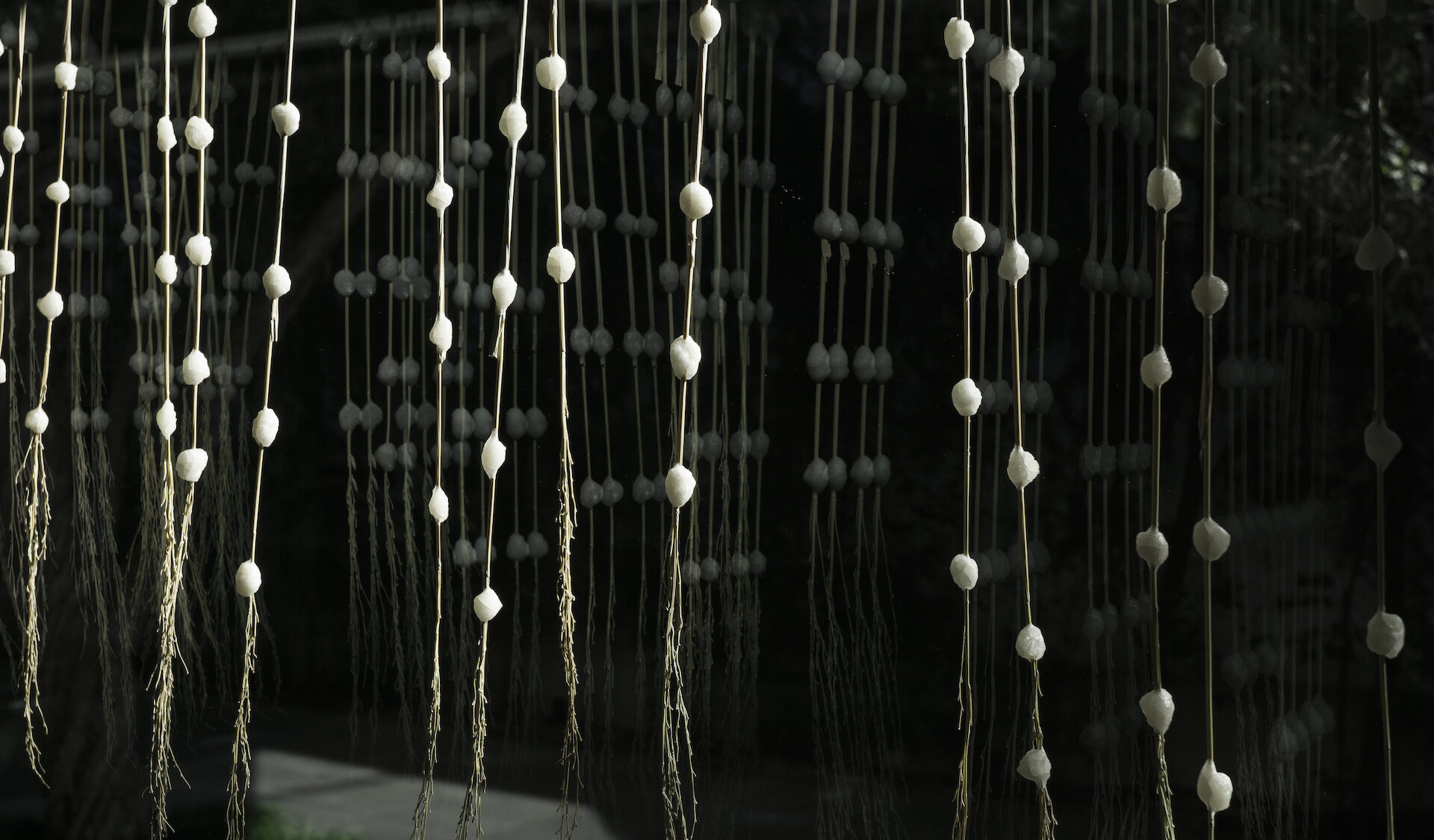

また東日本では、蚕の繭のかたちにして木にさした「繭玉」(まゆだま)を飾り、養蚕に関連の深い道具などをいっしょに飾る地方もあるという。

蚕の安全を祈願したり、五穀豊穣を願ったり花を待ち侘びたりと、どれも祈りが形になった餅花が、地方や生業ごとに特徴を持っている。

今回Shiharaのファサードにあつらえた餅花は、農業を生業にしている方ならどのような思いを持って仕上げるだろう、と想像しながら拵えたしめ縄の餅花だ。

しめ縄の縄は雲を表し、垂れる稲藁は雨を表しているという説があるが、農家の人なら当然素材には藁を選ぶだろうし、そこに餅をつけることも餅の原料が米ということを考えれば、全く無理がない。

それに米作りには、「米」の字が表すとおり、八十八もの手間がかかるといわれているので、垂らす藁は88本にするなど数字にも願いを込めたりするのではないだろうか。

お正月飾りの多くは祈りが形になったものであり、けっしてデザイン優先になってはいけないように思う。

芯だけにした餅藁を綯って雲を浮かべ、稲藁に餅をつけ雨を降らせた、しめ縄の餅花。

農耕民族だった日本において、大地を潤す雨は神様からの恵みそのものであっただろう。

One of the most transcendent Japanese New Year’s decorations is the rice cake flowers known as mochi-bana. In Hida Takayama, freshly pounded rice cakes are decorated like a flowers on branches growing from a stump. In Nagano, Kyoto, among other regions, rice cakes are placed on weeping willow branches to represent a bountiful harvest of drooping ears of rice for ine-no-hana and awabohiebo decorations.

In eastern Japan, mayudama, which are made in the shape of silkworm cocoons and attached to trees, are decorated along with tools and other items closely related to sericulture. Various prayers — from wishing the safety of silkworms, a bountiful harvest, or anticipation for flowers — take shape in mochi-bana, which are unique to each region and each livelihood.

When creating the mochi-bana on the facade of the Shihara stores, I imagined how a rice farmer would have created them. There is a theory that the shime-nawa ropes represent clouds and the hanging rice straw represents rain. Farmers would naturally choose straw as the material, and it wouldn’t be unreasonable for them attach rice cakes to it, considering that rice is the raw material of mochi. It is said that as much as 88 steps of labor are required to grow rice, so it is likely that they would put their wishes in numbers as well, for example, using 88 pieces of straws.

Most Japanese New Year’s decorations are a form of prayer. I believe that design should not be given the first priority. We made the mochi-bana on the shime-nawa ropes by twisting rice straws with only the core left intact to the floating clouds and making it rain mochi.

Japan has always been an agrarian society, and the rain that moistened the earth would have been a blessing from the gods themselves.